The (short) death and return of 'The Believer:' marketing a finite homecoming

Kennedy Coyne

November 2, 2022

In her book, "Standing Room Only," Joanne Bernstein writes that the central importance of marketing is to “bring an audience to the art and the art to the audience in ways that are relevant, meaningful, and compelling.” The recent “homecoming” story behind literary magazine "The Believer" — “killed” by an institution, then brought back to life months later by independent press McSweeney’s — epitomizes the significance of this marketing relationship between art and audience.

In October 2021, The Black Mountain Institute, an international literary center at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas which housed "The Believer," announced that they could no longer financially support the magazine, just shy of its 20th anniversary.

"The Believer" has a long history. Founded in 2003 by Heidi Julavits, Vendela Vida, and Ed Park, it was originally published under McSweeney’s. But in 2017 when McSweeney’s could no longer financially support it, they sold it to the Black Mountain Institute, under the leadership of new editor-in-chief Joshua Wolf Shenk (who’s perhaps most known for exposing himself in the bathtub on a Zoom call with staff in early 2021).

As a literary arts magazine, "The Believer’s" brand was different. They didn’t just publish poetry and fiction; they published feature essays and comics and interviews with celebrities and musicians. "The Believer" was accessible to most audiences with columns like Nick Hornby’s “Stuff I’ve Been Reading” or Peter Orner’s “Notes in the Margin” (where he writes about notes he find in the margins of books) while similar magazines were marketing more “high-brow” content.

"The Believer’s" content doesn’t just stand out. The words, 'The Believer,' scroll across the top of each issue in big block letters. The art pops and positions the magazine as though it were a comic book with illustrations on its covers such as, in its “Tick Tick…” issue, that of a man in black and white who appears to be writing a novel while laying in his bed in the middle of a colorful forest, or, the “Karmic Pillows” issue with a woman stopped at the side of a highway, looking at a deer the size of an airplane fittingly paired with text telling its audience that inside they’ll find Wilco-lead Jeff Tweedy interviewing himself.

When @thefineprintnyc reposted an excerpt of the press release, “UNLV Black Mountain Institute Realigning Outreach Initiatives,” in which the Black Mountain Institute stated that they could no longer financially support "The Believer," the corners of literary Twitterverse responded with lots of “oh no”s, “what a shame”s, and “R.I.P”s. Some even accused the Black Mountain Institute of killing "The Believer." Hundreds of what Mark Schaefer, in his book, Market Rebellion, would call “brand advocates,” or everyday folk, responded to the news with replies, retweets, and quote tweets, expressing their disappointment for what happened. In a lot of ways, followers of "The Believer" advocated for the magazine more than the actual magazine advocated for itself, at least publicly.

According to the press release, “[t]he decision is part of a strategic realignment with the college and BMI as it emerges from the financial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.” BMI positioned this move as a way to use the resources they did have to better align with their mission, one focused on serving and supporting underrepresented voices.

Despite this seemingly necessary strategic realignment, the timing of this change appeared rather suspicious as it followed the recent resignation of editor-in-chief Shenk who stepped down after the news of the Zoom exposure went viral.

In “The Believer was a Victim of Mismanagement and Neglect,” Nicholas Russell writes, “[A] mistake people make when talking about literary publications is thinking that they are common, easy to create, and easy to maintain. But places like "The Believer" are rare and exceedingly precious in a dwindling print landscape. Dedicated, high-quality spaces for writing and discussion about music, film, and are not easy to find, especially online. And, in this case, not even the stewards of the magazine can be counted on to fight for its continued existence. Many writers, including myself, would not be where they are without 'The Believer.'”

This incident with "The Believer: highlights a cultural issue in literary arts in which publications that seek to serve are often “mismanaged and neglect[ed].” How can an audience for a magazine like "The Believer" support and trust it if it’s been revealed that the institutions housing these literary arts perhaps cannot be trusted?

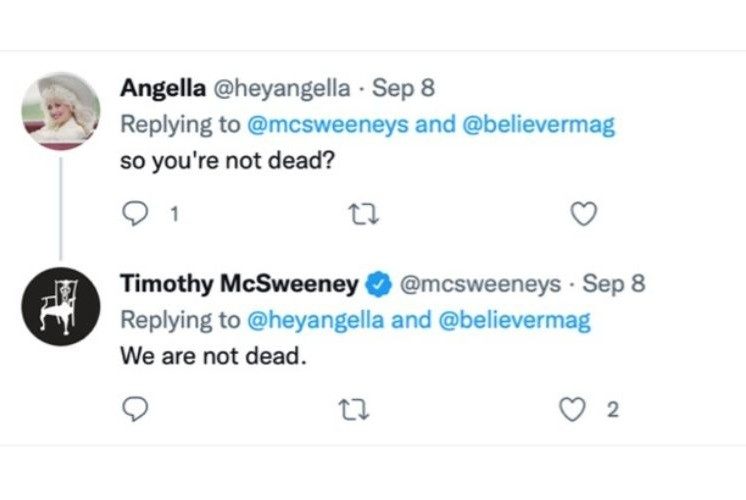

When, "The Believer’s: original publisher, McSweeney’s announced “The Believer is Coming Home,” seven months later, sharing that they would reacquire "The Believer," the gesture told its audience that they were heard. In Marketing Rebellion, Mark Schaefer writes, “Marketing is never about your ‘why.’ It’s about your customer’s ‘why.’” By taking "The Believer" back, McSweeney’s called out to the people who disbelieve in the “institution” and were able to be representatives for being an organization that looks out for its fellow literary arts community.

In order to make this reacquisition, though, McSweeney’s had to call back to "The Believer’s" audience for support, positioning it as a community endeavor. They shared a Kickstarter, “Bringing the Believer Home,” campaign across their social media platforms as well on their websites. Their goal was to raise $250,000 which would be used to pay contributors, staffing, shipping and distribution. The public responded to the campaign and pledged over $300,000. There was excitement for the rebirth of a magazine that people in the literary arts community thought had died. Despite potential financial challenges, McSweeney’s proved that they were invested in "The Believer" brand and in human-centered and values-based marketing. And, as Seth Godin notes in This is Marketing, people buy feelings, not products.

On September 8, 2022, McSweeney’s sent out a marketing email to subscribers stating, “Not to sound like your six hundredth political fundraising email of the day, but we’re still in shock. After a staggering array of twists and turns, a half decade away, and a Kickstarter campaign more successful than our wildest fever dreams, 'The Believer' is coming home this fall.” They offered a deal for a four-issue subscription of $49.50 as opposed to $60, pitched as a “celebratory sale.” This marketing email represents and encompasses the kind of excitement that McSweeney’s is using to get its audience to support and buy-into "The Believer."

A month later, "The Believer" posted across their social media platforms “ISSUE 140 IS COMING” as a reminder of the November 2022 “homecoming” issue that will be published under McSweeney’s. In a subsequent post, they told audiences that they would “be taking a tour through 'The Believer' archives” on Twitter “[A]ND offering up exclusive looks insider the new issue […]” on Instagram. They’re attempting to return to the magazine’s history in tandem with looking to the future—where they’re going and how they got there. But marketing seems to be over reliant on social media, and if success is measured in “likes,” the storm behind McSweeney’s re-acquiring "The Believer" has calmed. It hasn’t gotten the same kind of traction that it did when they first announced the “homecoming.”

That said, there is innate optimism just in the name of the magazine: "The Believer." McSweeney’s positioning this acquisition as a homecoming turns an otherwise dismal string of events into something that garners hope for other arts organizations—that organizations can support and look out for one another—that community exists.

In Marketing Rebellion, Mark Schaefer writes, “Despite the risk, taking a stand may be a vital opportunity to refresh an aging brand and find new relevance with consumers.” But so far, the campaign has been marketed to the magazine’s existing audience. "The Believer" is not rebranding. They’re returning to their original publishing house that sold them once before because they couldn’t afford to keep them. Although they have a devoted readership, that in turn, perhaps, doesn’t account for a new audience.

The market for the arts is fraught. Literary arts are arguably facing a more trying time as ideas that “print is dead.” In his 2018 article “Literary Magazines are Born to Die,” Nick Ripatrazone writes, “Radical passion often meets practical reality.” Even as McSweeney’s markets a homecoming and a rebirth and as The Believer claims “Like all good magazines, it has died a few times, but it always comes back to life, thanks to its faithful and devoted readership,” when does readership meet that practical reality? What if passion isn’t enough? When a marketing campaign is devoted to something that is finite, how do they garner continued excitement beyond this “homecoming” issue?

Kennedy Coyne is a graduate student in the MFA in Creative Writing program at Virginia Tech.