Orpheum ascending: Short, mid, and long-range planning for a historic theatre venue in Memphis

Liz Gray

April 25, 2024

Historical theatre construction: a brief history

The performing arts have long been a tradition at the cultural core of America, and the evolution of the art form helped to convert theatres into community centers as we know them today.

American theatre construction began as early as 1716 in Virginia and, as the Industrial Revolution boomed in the early 19th century, English-style performing arts venues began to blossom around the country. Then, with the end of the Civil War and the simultaneous rise of the transportation industry, these traditional theatres were converted to accommodate vaudeville’s traveling sets. Next, the hoi polloi was introduced to film, causing vaudeville theatres to fall out of popularity in the 1920s—venues were converted, yet again, into lavish movie palaces. By the 1960s, movie theatres began to fall into disrepair when the newest form of media, the television, entered the American living room. During the 1970-80s, communities started to grapple with the future of their aging arts centers, many of which had been converted and reconstructed numerous times for different entertainment purposes.

The Reagan-era appeals to Congress to abolish the National Endowment for the Arts prompted a reduction in public arts funding that tied many communities' hands concerning how to rehabilitate these cultural centers. Their choices were to 1) demolish the building, or 2) locally fund reconstruction. Communities had to decide if their historic venue held enough “preservation value” which “is predicated not only on the aesthetic quality and significance of a building's design, but also on its uniqueness and importance as a historical place or cultural symbol,” shares the University of Maryland architecture professor, Rodger K. Lewis. For many cities, it was the prudent, fiscally responsible choice to demolish these historic venues and rebuild for a more functional, communal future. For other cities, major renovation and reconstruction between the 1970s-90s was the path forward for historical preservation. In Memphis, TN, a group of individuals chose the latter.

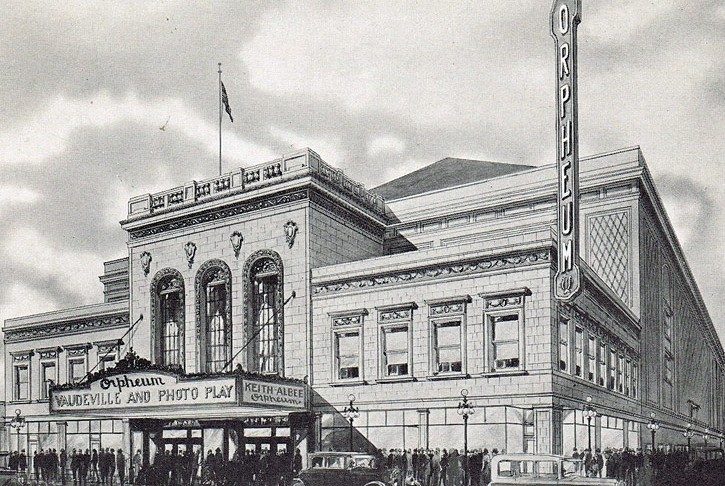

The Memphis Development Foundation was formed to save the remarkable Orpheum Theatre, which is part of the League of Historic American Theatres and was one of Memphis’ first buildings to be added to the National Register of Historic Places. Now restored to its 1928 glory, Vice President and Chief Operations Officer, Dacquiri Baptiste, plays an instrumental role in the strategic management of the historic space.

The continual repair and upkeep of historically designated venues carries a range of considerations that require short, mid, and long-range planning. Baptiste must chart future paths for major systems replacement, which means that budging for large-scale projects is a study in forward thinking, architectural collaboration, preventative maintenance, and strategic alignment.

Short, mid, and long-range planning

Short-range planning generally concerns the management of more immediate goals. This can include urgent day-to-day tasks and range up to annual planning. For a historic theatre, this could include resealing a leaky toilet or ordering and remounting a replica antique mirror. Short-range planning might only require a few people to handle the problem, is often compliance-oriented, and can be more immediate and/or less strategic in nature.

Mid-range planning lives in the 3-to-5-year range of strategic thinking processes. This may include projects that are more complex and expensive for older venues, such as replicating and reinstalling aged carpeting or rewiring a vintage marquee with rare electrical components from the 1970s. The planning process for mid-range projects often requires interdepartmental communication, milestone setting, accountability assignments, and board support.

Long-range planning involves projects surrounding the major structures and/or systems of a historic venue and are usually planned 7-to-10 years before implementation. These are undertakings that require large-scale fiscal support from donors, strategic timeline negotiations, committee planning processes, project monitoring, and public information dissemination. If the roof of a 100-year-old building needs to be rehabilitated or all the aging plumbing needs replacing, there are a variety of stakeholders who must work together to ensure the process runs smoothly from the initial analysis until the final installation.

Strategic planning for historic venues

Short term planning efforts at the Orpheum Theatre are incorporated into the annual operating budget as ever-evolving, individual line items, Baptiste shares. These short-range budgeting categories cover building equipment purchases (think recycling bins), general repairs (think repainting), janitorial supplies, building service contracts (think boilers—with HVAC systems holding a separate line item all its own), stage equipment, and utilities.

One particularly interesting line item is dedicated solely to lightbulbs. Surprisingly, lightbulbs span short, mid, and long-range planning at the Orpheum! This line item reveals deeper considerations about how historicity factors into strategic upkeep. With the historical designations that have been granted to the Orpheum, they can’t simply walk to the corner store and grab a box of bulbs—they must get historically accurate bulbs from specific vendors.

In the short-term, Baptiste can annually plan that she will need a certain number of lightbulbs that meet the design parameters of their historical designations. In the mid-term, she must maintain and negotiate contractual relationships with the vendors that supply the specialized bulbs. In the long-term, the Orpheum’s lightbulb usage concerns the larger infrastructure of the building. In 2022, the Biden administration set strict energy metrics for lighting, which effectively halted the sale of incandescent bulbs. While there has been a positive correlation to the alleviation of the United States’ high energy emissions with this legislation, Baptiste shares that these energy regulations have had industry-wide ramifications as performing arts centers transition to meet new energy outputs.

For modern arts centers, compliance may only require them to swap out some bulbs; but, for the Orpheum, not only do their vendors need to recreate the vintage bulb design into LED format to meet both historic designation regulations and new governmental efficiency requirements, but, additionally, all the historic lighting fixtures wired into the Orpheum must now accommodate modern energy metrics. The catch? LED bulbs in historic fixtures do not allow for a smooth fade to darkness in the theatre, which Baptiste notes is essential to the magic at the beginning of a performance. Fixing this transition to blackness at the top of a show has become one of the Orpheum’s long-range projects. This will require adapting the entire internal electric infrastructure of the nearly century-old building to allow for the new energetic output requirements while satisfying the aesthetic values of theatrical performance.

Like the long-range lighting project, Baptiste has 5-year plans and 10-year plans to address a variety of other mid and long-rang initiatives, respectively. Since historic venues have specialized building needs due to their age, she has developed lists of all the major systems in the Orpheum Theatre (as well as in the Halloran Centre, which the Orpheum Theatre Group also owns) which she has subsequently integrated into preventative maintenance plans. Baptiste begins planning for replacements well in advance of the expiration of those systems, knowing that costly and time-consuming renovations “can be a moving target.” Longer-range projects require Baptiste to consistently ponder: what makes the most sense and is the best thing for the building at this juncture? She answers that question through consistent evaluation of infrastructural needs, prioritization, risk management considerations, and stakeholder perception of the space.

To fiscally plan for longer-term capital maintenance needs, Baptiste works closely with the Orpheum Theatre Group’s development and financial departments, as well as the board-based building committee. She is a major proponent of working collaboratively to break down informational silos concerning major fiscal undertakings. From her perspective, these cross-departmental conversations are the only way future-oriented budgets can be created to support the realities of the aging building.

With the 100th anniversary of the Orpheum Theatre approaching in 2028, Baptiste’s short, mid, and long-range strategies will continue to support the future of the historic venue. Here’s to hoping for a 200th anniversary celebration in 2128!

The TLDR version of short, mid, and long-range planning that I have gleaned from Baptiste’s intentional strategizing for infrastructural maintenance of historic venues is:

- Create preventative maintenance plans

- Start early on big projects

- Budget, budget, budget

- Evaluate and prioritize for safety and external perception

- Build a team to help plan for fiscal realities so they can be actualized

- And remember: “once the walls come down, all bets are off,” says Baptiste — so, be ready to pivot if you run a historic venue!

Liz Gray is a graduate student in the M.F.A. in Theatre - Arts Leadership program at Virginia Tech.